I see sick people: Beliefs about sensory detection of infectious disease are largely consistent across cultures

Resumen

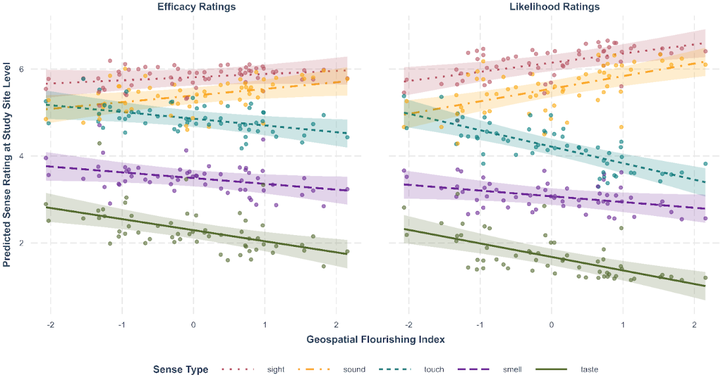

Identifying interpersonal disease threats is critical for effectively tracking and defending against infection. People hold lay beliefs about the types of sensory information that are most relevant for identifying whether others are sick with contagious illnesses. Are these beliefs universal, or do they vary along cultural dimensions linked with pathogen hazards? Participants in 58 countries (N = 19,217) judged how effective, and how likely they were to use, cues involving the major sensory modalities of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. Across countries, belief patterns were strongly consistent, suggesting a largely universal conceptualization of the role of sensory information for interpersonal disease detection. Results also support a safe senses hypothesis, with perceivers reporting that they would use senses that function at a distance—and thus reduce pathogen transmission risk—more than would be expected based on perceivers’ beliefs regarding the respective efficacy of those senses. Where cultural variation did emerge, this was captured by a cohesive set of socio-ecological factors, including human development, latitude, pathogen prevalence, and population density. Together, these findings reveal a shared lens through which contagious disease is assessed, one that prioritizes minimizing harm to perceivers, and may offer leverage for designing interventions to improve public health.